8 Points about AI Development Agreements that can be learned from the “Contract Guidance on Utilization of AI and Data

Furthermore, these materials, interim deliverables, and deliverables have high values and therefore both the

vendor and the user have strong intentions to monopolize/re-use them.

For example, if we assume the typical case of the vendor who generates a trained model using raw data provided

by the user, the intentions of the vendor and the user with respect to the vendor’s deliverables will conflict

as shown below.

▼ User’s Position

The user wants to monopolize the training datasets and trained models since they are generated largely from

the raw data that incorporates the user’s own know-how and trade secrets and since the user has paid a

commission fee [to the vendor] at the time of development.

▼ Vendor’s Position

Since both the process of generating training datasets using raw data and the process of generating trained

models using raw data use the vendor’s own advanced know-how and tremendous labor, and since the training data

and the trained model are reusable, the vendor wants to use them for other development applications other than

the contracted development project.

Therefore, a framework to reconcile these conflicting intentions is necessary.

So, how should this be handled?

With respect to this issue, I believe that the following type of framework can be used to reconcile [the conflicting intentions].

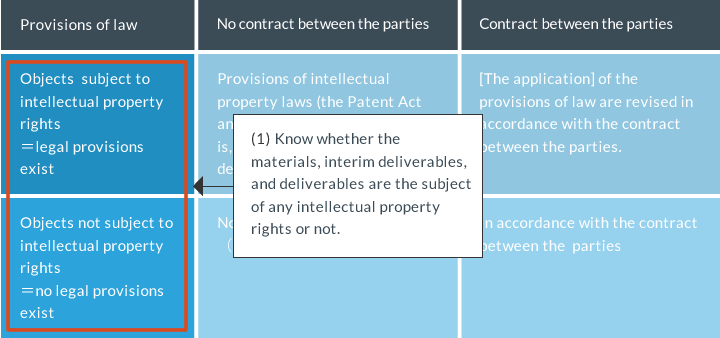

- (1) Among the materials, interim deliverables, and deliverables, know which are or are not covered by intellectual property rights

- (2) With respect to (1) above, know who has what rights under the default rules (i.e., the legal rules)

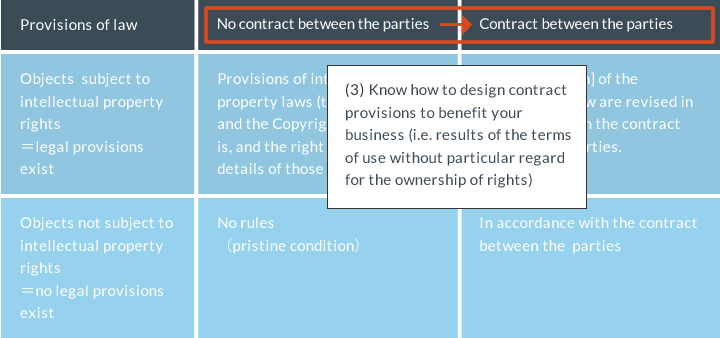

- (3) Know how to craft contract provisions that benefit your own company (without being particular about the “ownership of intellectual property rights”, prioritize the “terms of use”)

- (4) Know the limitations of the contract

▼ Let’s start with the general theory

First, before explaining this framework, I would like to explain the general theory about the relationship

between law and contracts.

In seminars and other presentations, when I ask whether [the audience] understands the relationship between

contracts and the law, most people understand that, in principle, when a promise is reduced to writing in a

contract, even though it may differ from what is written in the law, that contract takes precedence [over the

law].

On the other hand, there is an unexpectedly large number of people who are not aware that the provisions of

the law automatically apply to matters not stipulated in a contract.

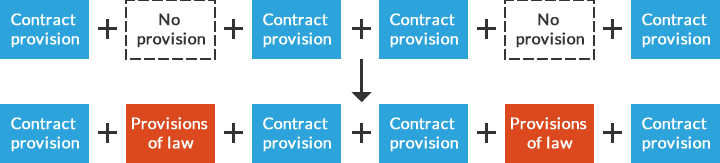

An illustration of this second point looks like this:

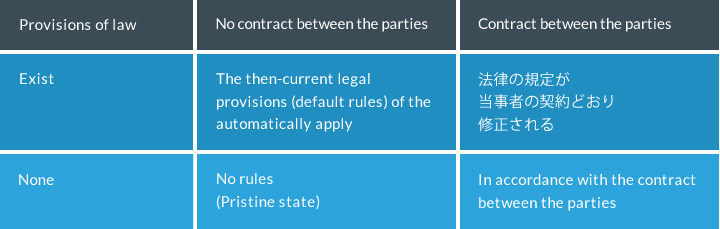

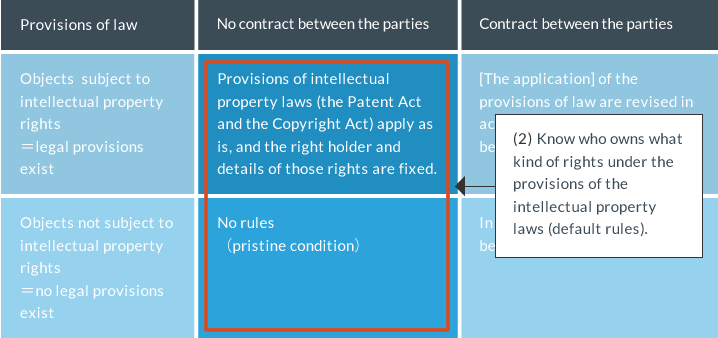

So, the diagrams above clearly show that when a matter is not stipulated in a contract, the provisions of law will automatically apply. Thus, if this “relationship between laws and contracts” is simply summarized in the matrix, the relationship looks as follows:

Let me provide a few concrete examples.

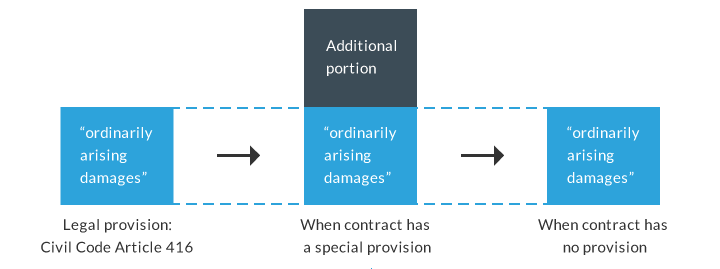

For example, let’s consider the case of an entrustment agreement which contains a contractual special

provision for compensation of damages and the case where such contract does not contain such a provision.

Although the scope of damages for failure to perform an obligation is prescribed in Article 416 of the Civil

Code, if there is a contractual provision that differs [from Article 416] (such as increasing the amount of

damages), then such contractual provision will take precedence over the law.

Conversely, when there is no contractual provision relating to the scope of damages, [such matter] shall be in

accordance with the provisions of law.

one more example.

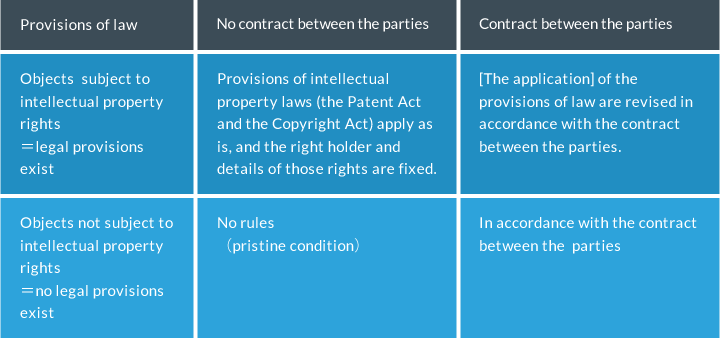

Let’s consider the scope of a hardware vendor’s use of sensor data that has been generated by a device

introduced into a user’s factory by the hardware vendor and sent to the hardware vendor with the user’s

consent.

To start with, since sensor data is not covered by any intellectual property rights, such as copyright, there

are no provisions under the current laws concerning who holds the right to use or who can use [such sensor

data].

So, this falls under the “no legal provisions exist” area on the matrix above.

Therefore, in a case where there is absolutely no agreement between the parties about the terms of use for the

data, there are also absolutely no rules at all, whether legal or contractual; this means that the situation

is a completely pristine state.

“Pristine state” essentially means that “the holder can freely use [the data]”; and in this example, it means

that the vendor can freely use the data while the user cannot impose any restrictions on the vendor’s use of

the data or have any right to demand the handover of the data.

Of course, where the parties have agreed about the data’s terms of use, [such use] will be in accordance with

such agreement. For example, if the parties agree that the data can be used for “the purpose of maintenance

and management of devices”, the vendor can only use [the data] within that scope; and if the parties add “for

the vendor’s improvement of the services and devices” to it, the vendor can also use [the data] within that

scope as well.

▼ How about the case of AI development?

Then, if you apply this general rule to AI development, it becomes like this.

First is the point “(1) Among the materials, interim deliverables, and deliverables, know which are or are not covered by intellectual property rights.”

This is due to the fact whether there are default rules (i.e, rules of laws) for terms of use and ownerships depends on whether [the materials, interim deliverables, and deliverables] are covered or not by intellectual property rights.

Next is the point “(2) With respect to (1) above, know who has what rights under the default rules (i.e., a legal rule).”

After grasping what items are covered by intellectual property right protection in point 1 above, you should understand the legal rules (the Patent Act, the Copyright Act, and others)relating to such covered matters in point 2.

Then, you should “(3) Know how to design contract provisions that benefit your company (i.e., without being particular about the “ownership of intellectual property rights”, prioritize the “terms of use.”

The problem is how to design the legal default rules or the “pristine state” in the contract.

Although this will be discussed in detail later, this design method is the key point in the way of thinking about the rights and intellectual property in the AI development agreement and one of the most important points in the AI Guidelines.

Finally, there is the point “(4) Know the limitations of the contract”.