8 Points about AI Development Agreements that can be learned from the “Contract Guidance on Utilization of AI and Data

6. Know-how

Various know-how is required when developing AI software. For example, this is know-how related to, among other things, the acquisition and selection method of raw data, the processing method into training dataset, an efficient learning method using a training program, and preparation of the trained model in the production environment.

(1) Whether or not it is covered by intellectual property rights

Since know-how is intangible information, it cannot be the object of a copyright; however, if know-how meets

the requirements for an “invention”, [such know-how] may be the object of patent rights. If the [know-how]

falls under the trade secret category (Unfair Competition Prevention Act, Article Paragraph 6) or the limited

provision data category (Revised Unfair Competition Prevention Act, Article 2, Paragraph 7), it will be

protected.

(2) Who has what rights under the default rules (i.e., a legal rule)?

Since know-how that does not fall under the trade secret category or the invention category involves no

intellectual property rights, no one holds any rights [to such know-how]. As such, both the user and the

vendor have no choice but to stipulate in a contract who can use the know-how and in what manner.

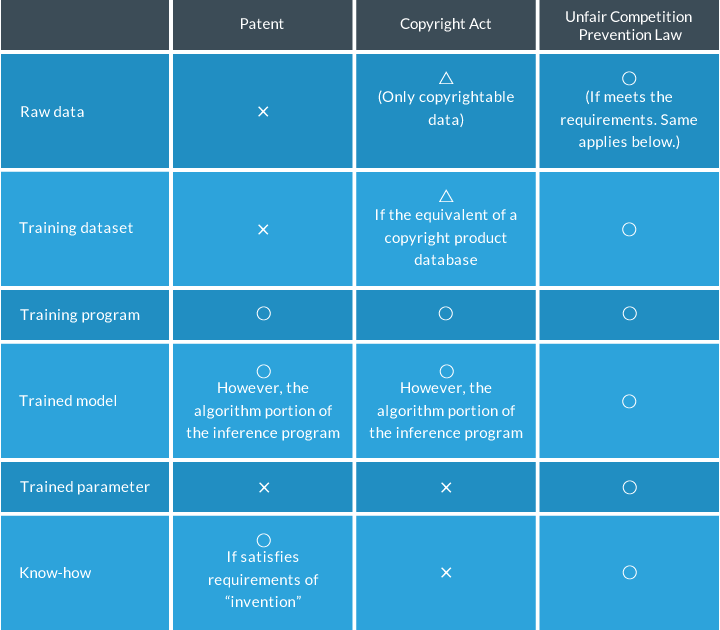

7. Summary

If we were to summarize the [information] above, it could look like the chart below. (Postscript added).

Note:

By the way, since the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s “Enhanced Environment for Open Data

Distribution Structures” (August 29, 2016, METI, hereafter the “METI material”) has a similar chart pertaining

to AI-related intellectual property rights (P. 82, hereafter the “Enhanced Environment Chart”), I would like

to provide a simple explanation of the relationship between the summary chart above and the Enhanced

Environment Chart. (Mr. Takuji Hashizume, thank you for pointing this out!!)

First, although it depends on the type of raw data, since certain kinds of data (for example, mechanical

operating data, sensor data, and factual data) do not include intellectual property rights, while other

copyrightable data (such as photographs, voices, images, and novels) involve copyrights, I have revised the

summary chart that first appeared with respect to (raw) data for consistency

with the Enhanced Environment Chart on this point.

Next, in the summary chart and the Enhanced Environment Chart, practically the same items are mentioned with

respect to “training dataset”.

In addition, if you look at page 78 in the METI material, I think that the “learning” in the Enhanced Environment Chart probably refers to the “training program” in the summary chart.

Further, judging from page 79 in the METI material indicating that “a trained model is an enumeration of

numbers calculated by a computer (matrix, etc.)…”, I think that the “ trained

model” in the Enhanced Environment Chart refers to the “trained

parameter” in the summary chart. (Obviously, this is not an issue of whether the summary chart or the

Enhanced Environment Chart is correct; rather, as explained before, it is an issue of defining “trained

model”.)

Moreover, although it is noted in the Enhanced Environment Chart (the trained

parameter section in the summary chart) that the trained model may be protected under the Patent Act

and Copyright Act, I personally believe that this would be very difficult for the reason given earlier (i.e.,

[it is] “a large string of numerical values automatically generated by the training program”).

Finally, judging from the explanation in page 75 in the METI material to “incorporate the model in the

application and use it as software”, I believe that the “use” in the Enhanced Environment Chart probably

refers to the “trained model” (an inference program that incorporated trained

parameters) in the summary chart. (This is confusing, isn’t it?)

Reference:

“Enhanced Environment for Open Data Distribution Structures” (August 29, 2016, METI)

3. Know how to craft contract provisions that benefit your own company (without being particular about the “ownership of intellectual property rights”, prioritize the “terms of use”)

By now, you understand the legal default rules for the 6 objects in AI development.

The next important matter is how to craft contract provisions that benefit your company premised on those

default rules.

Typical Deadlocked Pattern

In AI development agreements, a typical deadlocked pattern concerning rights and intellectual property is

shown below.

[User’s Position]

The training dataset and the trained model are generated using raw data that is filled with our know-how and

secrets and we pay a subcontracting fee for development. We have certain rights, don’t we?

[Vendor’s Position]

No, you cannot generate a trained model with only raw data. What makes a high-performing model possible is

largely thanks to our advanced know-how and intensive labor efforts in both the preprocessing of data and the

training process of model. We have certain rights, don’t we?

How should we think about this?

This type of confrontation mainly stems from the [position] of the user and the vendor that the

deliverables belong to their respective company, in other words, their persistent claims that the rights to

the deliverables should belong to their company.

So, as long as both the vendor and the user continuously persist in their claims of “who has the right”

(ownership of intellectual property rights) without any mutual resolution, the negotiations will take a

tremendous amount of effort and time with both companies ultimately losing their respective competitiveness.

In essence, there should be more contractual provisions than either party initially thought that can

simultaneously meet the needs of both parties since the business structures of the person providing the data

(the user) and the person generating the trained model (the vendor) are different.

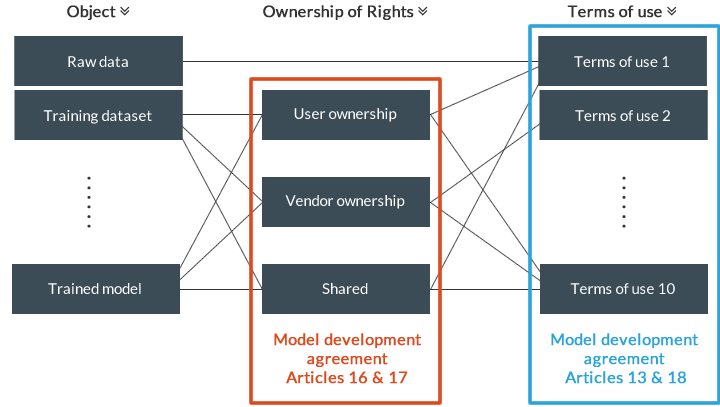

For this reason, the AI Guidelines suggest handling the “ownership of intellectual property

rights” and the “terms of use” separately and setting flexible conditions.

For example, with respect to the trained model, by (1) allowing the vendor to own the rights (ownership of

intellectual property rights) and then (2) prohibiting the vendor from using [the trained model] for other

than a certain purpose or for a competitive purpose for a fixed period after development, while allowing the

user free use of the trained model (terms of use), it might be possible to conclude an agreement that is

consistent with the mutual benefits of both parties.

In other words, this is a concept where the “terms of use” are “prioritized” than the “ownership of

intellectual property rights” of the objects by both parties.

To give an extreme example, even if your company holds no rights relating to the trained model and the

counter-party owns all of the right, if, as a result of the negotiations, a provision can be included in the

terms of use allowing the free use of the model without any restriction, including providing such model to

third parties, this would be virtually the same as holding the rights to the model. (Of

course,権利の譲渡の可否や権利者が移転した際の対抗力の問題など、「モデルの権利を保有しているのと完全に同じ」というわけではありませんが)。

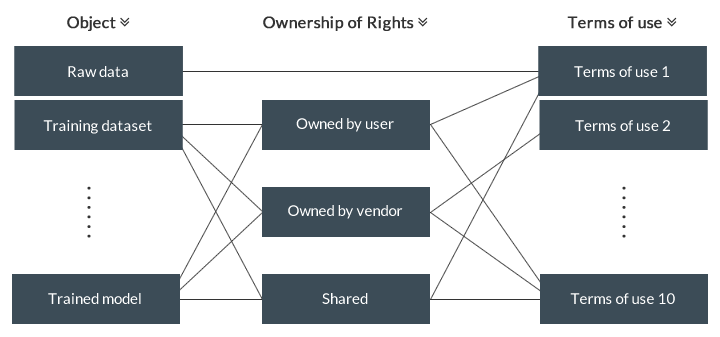

Concrete Approach

In this way, if one considers the idea “ownership of intellectual property rights” and the “terms of use”

separately, this would logically lead to fixing the “ownership of intellectual property rights” and “terms of

use” for all of the 6 objects mentioned. Moreover, the reason why the ownership of the intellectual property

rights for raw data is not mentioned in the chart below is that such raw data does not give rise to any

intellectual property rights under the current laws and stipulating [such ownership rights] directly in the

“terms of use” is sufficient. (Of course, the ownership of intellectual property rights of data that triggers

intellectual property rights, such as copyrighted products, will be problematic.)

In reality, there are probably many simpler patterns. The software development agreement for the development phase (model contract) appended to the AI Guidelines contains provisions for ownership of intellectual property rights in Article 16 and Article 17 and provisions for the terms of use in Article 13 and Article 18.